Many agencies at the national, state and local levels are working to address the nation’s drug and alcohol misuse crisis. While this provides numerous opportunities for individuals to receive support, efforts across these agencies are often not closely coordinated.

A new million-dollar award from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services agency, to Penn State’s PROSPER team is helping to develop connections between groups working on substance use prevention across Pennsylvania.

PROSPER is a substance-use prevention program that has been running for nearly two decades in Pennsylvania and Iowa. PROSPER — short for promoting school-community-university partnerships to enhance resilience — targets middle school students before they start using substances and helps them and their families build the skills needed to avoid substance use. Multiple studies have demonstrated that high school students in PROSPER communities are less likely to drink alcohol and smoke than students from non-PROSPER communities. Currently, PROSPER is working in 18 communities across the state.

Reducing supply and demand

Traditionally, PROSPER has focused on reducing the demand for drugs by equipping young people with the skills they need to avoid future substance use. Other agencies, such as the Pennsylvania Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and local law enforcement, focus mainly on reducing the supply of drugs within communities. These agencies use strategies like interdiction, drug take-back initiatives, and prescription drug monitoring programs.

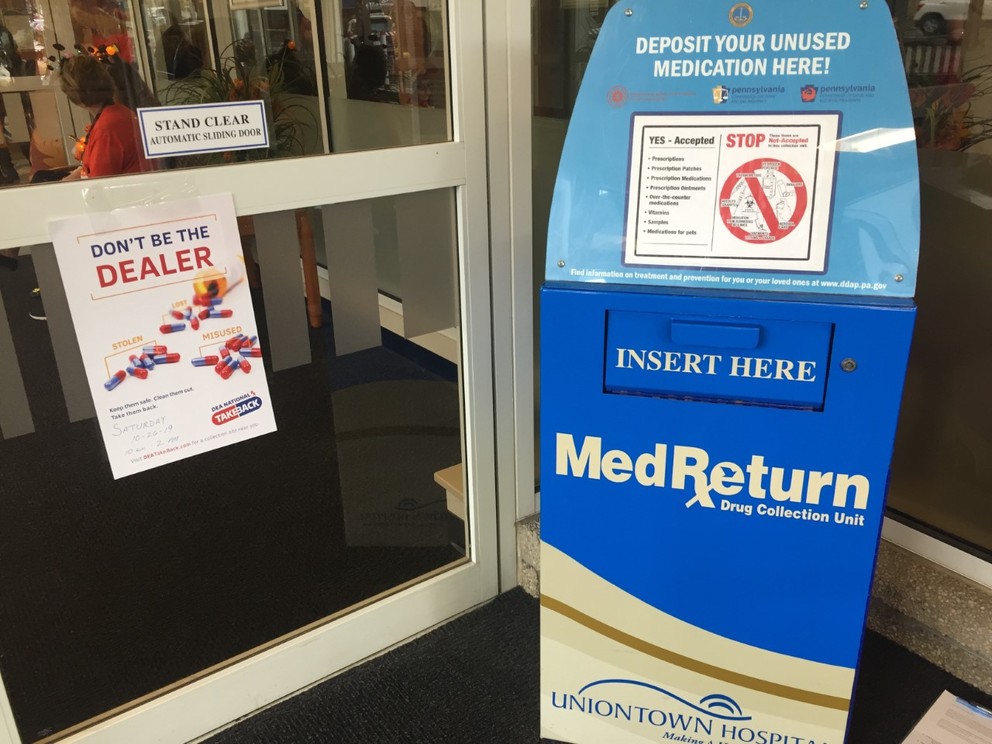

In this new project, the PROSPER team is seeking to improve the impact of PROSPER by joining with these agencies to incorporate innovative drug take-back boxes into their project.

“‘What could we do to make PROSPER even better?’ That was the question that led to this project,” explained Janet Welsh, research professor in the Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, and principal investigator on the project. “We knew that there was a whole other group of stakeholders working on the supply side of the substance misuse epidemic. Our lane has always been in demand reduction, but there is a whole other lane in supply reduction. We invited the drug take-back stakeholders to join the PROSPER team. We want to use PROSPER’s power to connect with different aspects of the population in order to enhance the drug take-back initiatives in our communities.”

Drug take-back programs

Once the PROSPER team coordinated with representatives of Pennsylvania’s DEA and Attorney General’s office about drug take-back policy and strategy, members of local law enforcement joined the PROSPER team. Collectively, they sought to improve the use of drug take-back programs and the quality of data gathered from the programs.

“We work very closely with, as an example, the Fayette County Sheriff’s department,” Welsh said. “The sheriff is terrific. He is on the PROSPER team. He even went to the White House representing PROSPER at a luncheon to promote effective tools for addressing substance use in rural communities.”

Drug take-back programs allow people to dispose of unused prescription medication without explanation or fear of questioning. Researchers report that people misuse prescription medications in part because the drugs are easy to obtain when they remain in homes after they are no longer needed.

Some people don’t want to throw or flush old medications away, but they do not know how to responsibly dispose of them. By incorporating education about drug take-back events and permanent drug take-back boxes, the PROSPER team are working to improve the use of take-back to reduce the supply of pain killers within the communities.

Because PROSPER is already working with youth across its participating communities, it has the reach to educate families about drug take-back options. As part of this same funding project, the PROSPER team has developed remote, online versions of some of their programs in order to continue to educate and serve families during the pandemic.

One difficulty with drug take-back programs involves gathering data about how well they work. There are many rules about take-back boxes to prevent the recirculation of the drugs and protect the privacy of the people turning in medication. For example, the boxes can never be opened, which can make it hard to know whether the boxes are collecting the most commonly abused medications, like pain pills. The only measurement of use that has previously been possible was weighing the boxes after they were filled, but there was no way to know what was inside.

Expanding the team, expanding the knowledge

In order to get better information without compromising privacy or security, the PROSPER team collaborated with Penn State engineering students. The students designed new, low-technology, low-cost boxes that can measure the date, time, and — thanks to a chute that allows box users to separate pain medications from other medications — the amount of pain medication being collected by weight. This additional information may help take-back stakeholders understand how to improve the use of boxes and, thereby, reduce the misuse of prescription drugs.

“The first prototype for the box is being used by the Penn State University Police,” Welsh said. “The deal that I made with them was that if they liked the data it provided, I would let them keep the modifications to the box. So far, they have been very happy with it.

“It’s been a very exciting project because it has allowed us to bring PROSPER together with the College of Engineering, students on campus, University Police, the DEA, the Attorney General’s office, and sheriffs in some of the PROSPER communities,” Welsh continued. “It has really made it a much broader and more diverse collaboration than it was. We love that.”

Derek Kreager, Liberal Arts Professor of Sociology and Criminology; Glenn Sterner, assistant professor of criminal justice at Penn State Abington; and Daniel Perkins, professor of youth and family resiliency and policy, are also investigators on this project.